WHAT I’VE BEEN WATCHING …

DEATH PROOF

dir. Quentin Tarantino, 2007

See, the thing is ... I kinda like Death Proof. Notoriously Quentin Tarantino's least critically acclaimed movie, and certainly one of his "smaller" outings, I think it actually represents an improvement over the vapid, too-showy, Saturday-morning-cartoon-from-Hell, Kill Bill. Dripping with actual verisimilitude, it coaxes us into feeling like real bystanders as we hang out with Jungle Julia and her comrades; you can practically smell the smoke of the old bar they spend the evening in, practically taste the liquor, practically feel your shoes sticking faintly to the floor. The music, as always, is deftly chosen and crackles with a lovely vinyl rasp. The mostly all-female banter is, if arch in that Tarantino way, surprisingly well-observed and written and fun. In contrast to the often flat, forced-feeling line deliveries and manufactured character emotions of Kill Bill, Death Proof's girls in this opening half have subtlety and range and their dialogue has a musicality that does Quentin proud. And lulled over the course of nearly an hour into a relative sense of safety, with only bare hints of the creepiness in store, when Death Proof finally unleashes its antagonist's fetishistic hunger on us, it is to pretty effectively shocking results.

But the problem with Death Proof, to some degree, is that it has a second half. And I don't know exactly what it is about this second plucky, devil-may-care group of girls and their ceaseless banter, but my attention always runs out of gas a bit come this section of the movie. It just becomes almost too much, with characters that become grating. In many ways it's loosely the same as the first half of the movie, except we have new information now; and that's interesting and fair enough. But this second group of girls, man. The first group was not a set of characters I found deeply endearing, but they were interesting as far as they went; the second set on the other hand can just be like nails on a goddamned chalkboard, as their goofy, irresponsible, dangerous plan to recreate a car stunt drags on, and on, and on, over-explained and over-set-up, before finally coming to the fruition that allows for the final showdown, and the climax of the film as a whole.

Now, once that final showdown kicks in, the movie more or less finds its way back into gear -- the old school car chase feels like a classic and satisfies viscerally, and the girls -- however much I dislike them -- getting the upper hand on Mike this time around is strangely cathartic, setting up a final moment or two to the movie that'll have you laughing and clapping (I mean, at least mentally) and leaving the film mostly satisfied. It probably would've actually worked better for me carved down by about 15 minutes or so -- particularly that second half -- but, the nitpicks aside, I do think Death Proof is a pretty good effort and an original, interesting creation with a lot going for it, despite some dead weight and irritating characters. It's far from my favorite of Tarantino's work, but it's also not my least; I tend to actually rank it in the middle somewhere.

25.03.20

The PARAGON

dir. Michael Duignan, 2023

"I like unicyclists -- in the circus."

The victim of a life-altering hit-and-run accident sets about teaching himself how to be psychic in order to tele-locate the silver Toyota Corolla that ran him down. If that sounds a little quirky and out there, well, it is, and for the first half of the film there's a charming balance between comedy and drama, fantasy and reality, as we follow tennis pro Dutch (an amusing Benedict Wall) in his attempt to unlock the full potential of his mind. Unfortunately, in the second half it really doubles down on the "fantasy" aspect of things and gets not only rather silly but convoluted as well. I think had the story remained a little more focused on Dutch and maybe the dynamic that develops between him and his psychic teacher Lyra (Florence Noble) -- then this could have been a winner. But as it is, it's more of a strong start that just gradually unravels into messy meh-ness. Certainly original, but it just doesn't really work as a whole.

25.03.20

Boiling Point (3-4x10月)

dir. Takeshi Kitano, 1990

(Minor spoilers). "Boiling Point" -- or in Japanese, 3-4x10月 -- is Takeshi Kitano's second film as director, and the first where he seemingly had complete creative control. It is one of my favorite Kitano films, maybe even my definite favorite. It follows with a Camus-like remove the actions, reactions, and generally thoughtless activities of a young man (Uehara) repeatedly causing his baseball team to lose (easily distracted by other things, his actual interest in the game of baseball seems negligible at best) after his coach is threatened and attacked by local yakuza. He and a dim-witted friend decide to travel to Okinawa and purchase guns with thoughts of revenge, but in addition to meeting a girl along the way, their trajectory is derailed by the crossing of paths with some other yakuza characters played by Beat Takeshi and a few of his regulars as his buddies/henchman. Roped into their bizarre, vaguely rapey misadventures, the movie from here sort of meanders playfully around with a mind of its own; a series of sometimes funny, sometimes violent, sometimes oddly poignant vignettes full of death and color. It's not neat, or plausible, or concerned with any of the things a typical movie is apt to be concerned with -- it is clear from the onset that we're in the hands of an auteur following his own somewhat cracked vision, wherever it may take him. The filmmaking feels largely instinctual, sporting an occasional apropros-of-nothing flash-forward -- but it's not aggressively weird, in a surreal sense (though there is a hint at the end of the movie that none of the events depicted may have actually happened). There's still just enough connective tissue to get you from A to B to C. But as in Camus' The Stanger, the steps don't seem to transcribe a conventional dramatic arc for Uehara or any of the other characters. Characters do things, because those are the things they do -- and in response, things happen, and those are the things that happen. It almost has a kind of anti-deepness to it that is hard to describe, a squeamishness about having any of its little adventures belabored with "meaning"; perhaps the lazy catch-all "Zen" might be appropriate here to convey the general flavor. Dry as uncooked rice and with a taste for the morally gray, Boiling Point for me is Kitano at peak Kitano-ness, and while I wouldn't necessarily recommend it as a starting point to someone just getting into him, I would strongly recommend it to someone who's seen one or more of his other, perhaps slightly more accessible movies (the Outrage trilogy, say, or Zatoichi) and wants to see him at his most strangely neutral, at his drily funniest, at his most blandly whimsical, and at his most creatively unencumbered.

25.03.20

CARRIE

dir. Brian De Palma, 1976

Been looking forward to this one for a long time and this was my first time seeing it, or any Carrie adaptation for that matter. The intensity of arch histrionics at work here is hard to understate; from the onset, the movie illustrates the hell of being an unpopular teenage girl with the subtlety of a semi-automatic machine-gun -- and that's nothing compared to its depiction of cruel hyper-religious mania. If the elaborate lengths to which Carrie's enemies will go to humiliate her at the prom is psychopathic and a bit implausible, it's also the movie's very over-the-top-ness in this regard that really defines it. A less grandiose Carrie would be too cliche -- it kind of sells itself on its own dark, ostentatious pomp and passion. I suspect the story is a bit thin compared to the book (I've never read) but if it's all a little one-note and drags slightly, it's still highly impactful in its bold, shamelessly operatic, very De Palma way. Highly cinematic and definitely one-of-a-kind.

25.03.19

GANDAHAR

dir. René Laloux, 1987

"Mindless loyalty gave them strength. I almost envied them."

A low-budget, hippy-trippy psychedelic odyssey with a surprisingly robust cast of well-known actors on voices, including Christopher Plummer, Glenn Close, Bridget Fonda, Jennifer Grey, Penn & Teller, and more, Gandahar (directed by René Laloux, probably best known for Fantastic Planet) has the energy of a codeine pill. With languid spacey music, hypnotizingly imaginative (if not overly refined) visuals, and a dreary, low-key narration from a vaguely prince-ly protagonist who feels like an 80s Saturday morning cartoon character on the needle, Gandahar is certainly unique and dreamy. It's probably not exactly best in class for this type of animated film of this era, but its dreaminess and the strength of some of its imagery and ideas still made it weirdly compelling for me, despite a thin story and barely-established characters / relationships.

25.03.18

The Cook, The Thief, His Wife & Her Lover

dir. Peter Greenaway, 1989

"Cannibal!"

(Minor spoilers). One of the primary instigators of the infamous "NC-17" rating, The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover is a film that made a huge impression on me as a teenager and that I revisit perhaps once every five to ten years. If its intriguing allegorical puzzle is a little over my head, that's half the fun of it; the movie certainly has a sureness of hand and a bold, confident style -- it knows exactly what it's doing, even if we as an audience don't always know exactly why it's doing it. Ostensibly about the wife of a crime boss (Helen Mirren, and the wonderful Michael Gambon at his most terrifyingly vile) sneaking off to enjoy the affections of a modest bookkeeper (Alan Howard) at their high-end restaurant, the movie is a surreal, nauseating, Biblical-feeling miasma of narcissism, sadism, gluttony, scatology, sex, secrecy, and torture portrayed as if through an ornate golden picture frame, with a simple but unforgettable score by Michael Nyman. Billed in titled chapters charting the days across the course of a week, wife Georgina's affair becomes increasingly dangerous and is eventually discovered, triggering a sequence where the lovers, still nude, must make their escape (with help from the Cook) in the back of a festering putrid truck of meat gone bad. The influence of the Marquis De Sade and Georges Bataille can be felt through all of this dressed-up debauchery, and while it doesn't go quite as far as their shocking excesses, it goes pretty far for 1989 and includes the upsetting torture of both children and adults.It all boils to a bizarre and appropriately preposterous, grandiose climax, that will keep you scratching your head for a while after the movie concludes. There's nothing else out there quite like The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover that I know of. The characters don't really make a whole lot of sense, but this sort of fits the odd fable-like quality of the whole thing, and for the most part, you just kind of buy into them as they are. Exquisitely unpleasant, with a formalist dreamlike quality all its own, that is certainly open to all manner of interpretation, with rich symbols and allusions everywhere in sight. Recommended.

25.03.15

Un Cœur En Hiver

dir. Claude Sautet, 1992

A loose inspiration for Neil Labute's soul-crushing depiction of pointless yet specific cruelty in "In the Company of Men", Claude Sautet's own Un Coeur En Hiver ("A Heart in Winter") from six years earlier likewise deals with some love triangle gamesmanship that doesn't bode well for any of its constituents. Where Labute goes in with a hammer, though, Un Coeur En Hiver maintains a cool, quiet, French subtlety throughout, slowly surprisingly us with nonchalant admissions about or from its primary characters in regards to each other. It's a subversion of the typical love triangle, and deeply effective in its quiet heartbreak. This movie made made me a huge fan of French actor Daniel Autiel, and of his many excellent performances, this is one of his best; and Emannuele Beart is also at her loveliest and most charming here. A smart, thoughtful, hypnotic character piece that goes against expectations and lands in unusual destinations.

03.14.24

MARIE ANTOINETTE

dir. Sofia Coppola, 2006

“Let them eat cake!”

Injecting anthemic dream-pop where classical music would normally be, and embracing a hypervisual style intended to show almost nothing other than extraordinary excess in every shot, Marie Antoinette charts the slide into opulence of the young woman bethrothed to (equally young) Louis XVI of France; who, unfortunately for Marie, seems to have no sexual interest in women, greatly delaying the delivery of an heir to the throne -- and thereby threatening Marie's position itself.

The movie's strong suit is in the way it highlights (via showing, as opposed to telling) how these two young sovereigns are really just a pair of kids in way over their heads, and how Marie in particular is little more than a show-thing and brood-mare. It's not dark about it though, concentrating as it does on the wonder and splendor of Marie's circumstances, perhaps to fault.

While Louis XVI and Marie manage a friendly if somewhat remote relationship, Marie's indulgences continue unabated, doing their part in leading to civil unrest and violence, that culminates in herself and the Dauphin of France having to flee home. I'm the furthest thing from a history expert on any of this, but it seems to me this is exactly where the story of Marie begins to get dramatically interesting, as both she and Louis XVI are eventually beheaded in France's transition into a republic. While the revolt is established, none of its consequences are followed through on or depicted, so nothing of substance or import really breaks through into the menagerie of Marie's privileged life, except for perhaps in a modest closing shot showing an interior room of their abandoned palace in disrepair.

Mesmerizing to look at, but at two hours, with minimal plot, it wears a bit thin and perhaps overstays its welcome a tad, as Marie herself is not a particularly interesting character, excepting her circumstances. It's mostly about a girl being a girl in the most unusual circumstances of the very highest class, and a mostly drama-free illustration of her utter insulation in that ethereal world of excess and beauty.

25.03.14

NOSFERATU (2024)

dir. Robert Eggers, 2024

Aren't we yet past the point where movies set in foreign countries inexplicably have the protagonists speaking English? I can read. The English-speaking feels particularly awkward when we're introduced to ze count and his nearly Sesame-street-like vampcent. Vun! Two! Tree! Seemingly suffering from the delusion it was laying some Heavy Horror on its audience, I found myself groaning and snickering with unintended laughter at Count Orlok's ridiculously guttural utterings, overplayed to the point of camp by a miscast or at least mis-directed Bill Skarsgård. Feeling very much like a movie made for (young) teenagers, Nosferatu proves surprisingly childish and unimaginative in its suspense/horror cues. The music, the visuals, the story beats, the editing -- they're all about what you would expect, nothing more, nothing less; no surprises. As if on a mission to reiterate the source material while extracting nothing new and adding nothing of value, the movie plods along in blue and orange light accompanied by high-key violins. Gasp! Rats! Gasp! Waking from a dark dream! None of Herzog's understanding of the eerie dreamlike nature of the original film is present here, and certainly none of Klaus Kinski's astonishingly weird, quasi-sexual charisma as the Count. Just campy, predictable story beat after yawn-inducingly campy, predictable story beat. Try as they might, Nicholas Hoult fails to engage as the absurdly tittering baby Thomas Hutter, as does Lily-Rose Depp as his wife, the melodramatically prescient Ellen Hutter -- and by the forty-five minute mark, a significant feeling of tedium had set in, for me, so the forward-skimming began. This is about the point at which we get a slight breath of fresh air in the form of Ralph Ineson and Willem Dafoe, as a doctor and professor tending to the maladies of the increasingly erratic Ellen Hutter (which, for their part, quickly become a comical "greatest hits" of every possession/exorcism-oriented cliche you've ever seen). Dafoe's exposition of the supernatural quickly becomes tiresome and patronizing to the audience and includes spooky old-timey forewarnings such as "A dread storm is rising!" NOT A DREAD STORM! GOD, NO!

The final act turns up the sexuality and gore, culminating in a nicely gruesome death scene for Count Orlok, but by this time the damage is done, and a few vaguely inspired moments and images aren't enough to salvage the languorous, hollow whole. I don't know what happened to the originality and vision and keen eye/ear for mood that Eggers brought to The Lighthouse, but he needs to find his way back to it. To me this felt like an entirely needless made-by-committee-style horror remake, containing very little that I can imagine exciting or hypnotizing any viewer over the age of twelve.

23.03.08

THE NORTHMAN

dir. Robert Eggers, 2022

Hokey and overrated, Robert Eggers' 2022 misfire The Northman unfolds like the plot of a video-game, replete with mini-bosses and a final boss battle. Heinous looking CGI mars his visual palette, and while there are memorable images amidst the gunk, it's borderline shocking how bad some of this movie looks. Alexander Skarsgård bores as Amleth, a viking lad whose father is massacred, an act for which he vows revenge; there is simply nothing to like or invest in with this character, and his paramour, Anya Taylor-Joy's Olga, offers very little as well. The plot twists are all visible a mile away, and I found myself just wanting the whole turgid affair to be over by the two-thirds mark. I was a big fan of The Lighthouse, but The Northman is substandard fare, and while I can't pretend my opinion here is a majority consensus, I hope that Eggers rebounds from this tiresome dud.

23.03.08

THE LIGHTHOUSE

dir. Robert Eggers, 2019

"Alright, have it your way. I like your cookin’."

(Spoilers, kind of). Robert Pattinson -- iffy accent or no -- has rarely been as compelling to watch as he is here, as Thomas Howard, a man who takes up residence/upkeep of the titular lighthouse with senior keeper Thomas Wake -- an absolutely unforgettable, iconic Willem Dafoe at his most scenery-chewingly piratey. Shot in utterly mesmerizing black and white, on a signature Kodak 35mm film in an unusually boxy 1:19:1 aspect ratio, the film has a look like no other, and thanks to complimentary and equally exquisite sound design, the movie thoroughly transports one into its eerie, forlorn setting. Vicious gulls, sinister mermaids, and an increasing sense of isolation and doom overwhelm poor Thomas Howard as he tries to decide whether he and Thomas Wake are perhaps one in the same. Despite its unerring creepiness, Eggers also manages to inject a welcome and disarming humor, as the two bizarre characters play off of one another in sometimes platonic, sometimes antagonistic ways. The whole thing spirals somewhat expectedly into open-ended surrealism -- and a frenzied, breathtaking climax that will stay with me for a long time. Ambiguous, but exceptional and recommended.

25.03.07

Violent Cop (その男、凶暴につき)

dir. Takeshi Kitano, 1989

Originally to be directed by veteran yakuza filmmaker Kinji Fukasaku (particularly well-known since for Battle Royale), scheduling conflicts caused him to hand off the project to lead actor Takeshi Kitano to direct. Kitano at this time was a humongous celebrity in Japan, known almost exclusively for screwball comedy, and given the director's reins, decided he wanted to take the movie in a darker, more serious direction. The end result is a bizarre mish-mash of subtle humor and dark dramatic turns, some of which are quite shocking. While the movie is ostensibly about the quintessential "cop who plays by his own rules" (a la Dirty Harry), Kitano brings a truly bizarre sense of pacing, and makes unusual, borderline surreal choices about what details to emphasize and which to gloss over. Shots you might expect to last a second or two will linger for 10-20 seconds, and scenes that you might expect to be quick throwaways will linger amusingly on and on (and on), seemingly just at the director's whim, almost as if teasing the audience. This might annoy some viewers but all goes a long ways to laying the groundwork of what would quickly become Kitano's signature moviemaking style, which I love and which is unlike that of any other director out there. "Aggressively nonchalant," could be one way to attempt to describe it; when moments of violence happen (and they often do) they unfold with the same mundanity the director might allot to a character eating a piece of cake. Stuff just happens, with a Camus/The Stranger-like existential emptiness; it's sort of the antithesis to the John Woo style of operatic hyper-violence. Similarly, characters themselves are uncomplicated conduits of pure action and reaction -- they are more like surreal puppet-people than rich, plausible human characters; their arcs feel predestined and inalterable, and the movie itself has a kind of overarching resigned malaise that speaks to this.

For me, it's a truly unique style and it all makes for mesmerizing viewing. With Violent Cop specifically, our no-fucks-given titular protagonist is watching over a mentally challenged sister while slowly getting roped into a drug-related murder investigation that will put him on the bad side of some yakuza and leave him questioning a close friendship. But the details are pretty incidental; it's more about its strange, vaguely dreamlike style, than the nuts and bolts of the plot. Highly recommended; let it hypnotize you on its own terms and rope you into Kitano's bizarre filmic world.

25.03.06

The Brutalist

dir. Brady Corbet, 2024

(Some spoilers...)

Adrian Brody, still struggling fifteen years on to one-up his unforgettable turn as 'Royce' in Nimród Antal's 2010 classic film Predators, stars here as some architect from the olden days who built block-ish looking stuff. Ok; architectural history isn't my strong suit, but it turns out that's okay, because I was halfway through viewing The Brutalist when an Intermission-inspired fit of Googling seized me and revealed that Hungarian-Jewish protagonist László Tóth did not actually exist. The poorly educated among us would be (hopefully) forgiven, at this point in the film, for being surprised by this -- with its air of historical seriousness and frequent allusions to real-life places and names, the first half of The Brutalist oozes the rich plausibility of a biopic destined for Oscar-town. Early on in the going, Brody offers up a truly compelling performance as a celebrated architect, Holocaust survivor and U.S. immigrant -- surely this was based on a real person that he must have studied with great care, for Brody to inhabit him with such convincing depth (like when he portrayed Wladyslaw Szpilman in Roman Polanski's unforgettable film The Pianist from 2002)?

But nope -- László is a fiction, and he's not the only pseudo-historical figment here, as Brody is surrounded by memorably believable supporting performances from Guy Pearce as pretentiously self-important wealthy patron Harrison Lee Van Buren, along with Joe Alwyn and resident "guy who seems to be in everything lately" as his snaky son, and Felicity Jones and Raffey Cassidy as László's sickly wife and seemingly mute niece who are finally able to follow him to America from abroad. The other real "how about that?" moment for me around Intermission/Google-time was realizing director Brady Corbet was "the other kid," Peter, to Michael Pitt's terrifying Paul in the 2007 home invasion favorite of mine, Funny Games (U.S.) by Michael Haneke. How far he's come since breaking Naomi Watts' eggs, with, as far as I can tell, only one feature film prior to this ambitious, expensive-seeming epic (2018's Vox Lux, which I may have to track down).

Corbet's youthful days as an actor aside, all this blathering on is just to acknowledge how believably the first half of The Brutalist resonates with the feel of actual American history, dripping as it is with careful period detail -- and frankly, I'm not sure I've ever seen such a convincing non-biopic/biopic stunt pulled before. So that's certainly something.

Then, Intermission and Googled revelations aside, we venture into the second half of the movie, and things start to get a bit ... weird. I suddenly began to feel a lot less persuaded by the veneer of authenticity, particularly around the characters, whose actions and relationships were becoming strained and unmoored in odd ways that felt a trifle nonsensical. Had the movie been this unconvincing all along, I wondered? Had Googling spoiled it for me? Not quite ... the movie definitely seemed to be slipping into a more intentionally dreamlike terrain, pulling the rug out from under me all on its own ... but if it was an admittedly neat trick, to what effect/purpose did it aspire? Since it was not in fact a historically accurate biopic of some kind, where was this all going exactly?

Well -- I finished it hours ago, have been thinking about it since, and I'm still not sure. In fact I'm not convinced the movie itself is sure. I'm certainly persuaded to feel there are fancy allegories at play, or at least the pretense of such, with all the strange xenophobia that begins to come to the forefront in the second half, and a bizarre man-on-man rape that starts our train-ride into crazytown and which seems to maybe be suggesting something about America's appropriation of other cultures ... but, honestly .... ? The second half of the movie seems to have big ideas, but it also seems, to me, unsure of what exactly to do with them. I gather skimming over some of the reviews out there that comparisons have been made to There Will Be Blood, but while both involve historically accurate period pieces with Big Themes that unravel into somewhat dreamlike territory, I'm harder pressed of what exactly to make of The Brutalist, and yet have none of the sensation that I did with There Will Be Blood of immediately wanting to see it all over again. To be honest, by the end of The Brutalist, the whole affair was proving a bit of a chore, and there was a sense, for me, of the whole thing collapsing under its own weight. I was much less glued to the screen than I was with TWBB, and ultimately not as invested in the characters, whose erratic, meandering behavior just begins to seem erratic for its own sake.

It could be that I simply do not yet understand The Brutalist; I like weird things, so its weirdness could theoretically grow on me I suppose. Maybe it's just over my head. Or maybe it doesn't matter that it doesn't resolve neatly. Or coherently. Or enjoyably. Uh, well -- wherever the chips fall, it's a film that will require some further processing yet. But I have a bit of a sense of it too desperately wanting to *be* a conversation piece and being constructed with that goal in mind, and I'm not immediately persuaded of the value of the film's unusual departure from faux-biopic to surreal fable. It was certainly original and willing to take some strange chances, but as it stands, I'm not sure they really pay off.

All in all: it's just a really mixed bag. What begins as an extremely compelling, historically detailed, marvelously acted character study, devolves into meandering, unpleasant, arguably masturbatory weirdness that, while coldly interesting at its best, isn't consistent or coherent enough to be particularly rewarding or enjoyable on the whole.

25.03.05

Anora

dir. Sean Baker, 2024

Winning the Oscar for Best Picture among other things just the other day, Anora mostly charts a single night/day in the aftermath of an impulsive marriage between an exotic dancer and the spoiled brat son of a wealthy Russian family. It unfolds with an unrelenting intensity and a host of grating -- but plausible -- characters that reminded me a little bit of 2019's Uncut Gems. The chief problem for me was that there is nobody much to root for, except maybe, in the end, Yura Borisov's hapless Igor; so it becomes an exercise in watching obnoxious, thoughtless people suffer the consequences of their obnoxiously thoughtless decisions, on both ends of the class spectrum. It's a well-made exercise as such, though, with excellent performances from the entire cast. A memorable enough experience as far as it goes, but one that mostly left me reminded of how much I fundamentally dislike humanity and the entire inequitable global classist system in which in writhes.

25.03.04

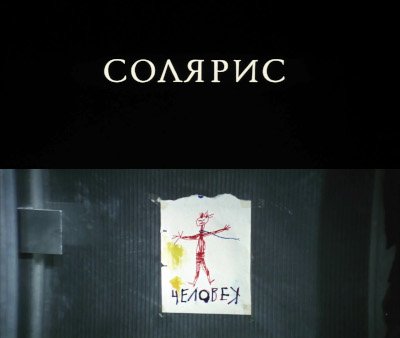

Solaris

dir. Andrei Tarkovsky, 1972

"We don't need other worlds. We need a mirror."

At long last I managed to finish Solaris in full. I found it visually enchanting, hypnotically paced, unusual, creative, head-scratching, pretentious, a bit dull, and (in ways) highly memorable, all at the same time. Natalya Bondarchuk shines as Solaris space station's chief resident ghost, Hari, an ex-wife of space cadet and psychologist Kris Kelvin, who is sent to Solaris to assess whether its mission should continue in the face of mass onboard hallucinations and other problems. You'd be forgiven for forgetting he's a psychologist, since he doesn't remotely act like one, and you'd be forgiven for forgetting his mission, since he does almost nothing to sensibly further it. He pretty quickly becomes preoccupied wandering vaguely about and dealing with a powerful personal "hallucination" of his own. A problem I have with the movie generally is that nobody acts like anybody would, really, in a plausible way. With the exception of the intriguingly vulnerable Hari, the characters all simply feel like mouthpieces for Tarkovsky's quasi-profound meandering dialogues, and -- for as desperately as Solaris wants to be A Serious Work of Art -- they are all far too vague and hazy to be deeply thought provoking. The mood and tone, however, and the spectre of Kelvin's past in the form of an alien/person, do create an atmosphere conducive to thought and feeling, and with all the space it gives you to ruminate, it becomes that sort of movie where you can maybe get out what you're willing to put in. Overall, for me -- I neither loved nor hated the film; I appreciate it for its philosophical ambition and somber, interesting visuals, and its anti-commercial pacing and cryptic, dreamy tone -- but I also don't feel it did particular justice to those things, with its threadbare story and its largely wooden, unrelatable, and difficult-to-connect-with characters, who tend to feel as if they're acting and speaking at random most of the time. An interesting experience.

25.03.02

Glengarry Glen Ross

dir. James Foley, 1992

"Always be closing."

(Minor spoilers.) Adapted from the stage play by David Mamet, James Foley's Glengarry Glen Ross is, like Reservoir Dogs, another 1992 example of absolutely pitch-perfect characters delivering absolutely pitch-perfect, testosterone-heavy material. Boasting in particular what I still think is Al Pacino's best performance, everyone in this film is perfectly cast and absolutely shines, from Ed Harris as the embittered shadow thief, to Jack Lemmon as the desperate, outdated old-schooler, to Kevin Spacey as the weaselly but unflappable company man, to Alan Arkin as the browbeaten loser, to Jonathan Pryce as the vulnerable would-be client, to of course Alec Baldwin's unforgettable turn as the Big Dog sent from downtown on a "mission of mercy" -- they all turn in their absolute best. Talky and chewy and quotable in the best way and confined mostly to a couple of primary settings (mainly the office, with a few scenes at a bar across the street and one in a client's home) the time nevertheless flies by, propelled by the non-stop theme-rich, character-building dialogue. If you've never seen this one before, queue it up and prepare for a treat. While I'd be fascinated to see another version of Glengarry with different actors (a recent Broadway version sported the likes of Bob Odenkirk, Bill Burr, and Michael McKean) I'm pretty sure this, for me, will always be the definitive version. It's small scale and not particularly showy, but it doesn't need to be, and as far as adapted plays go, it holds up as a nearly perfect piece of movie-making in every respect.

25.03.02

The Shape of Things

dir. Neil Labute, 2003

"This is f*cked."

After a brief sojourn into directing someone else's story with the 2000 misfire Nurse Betty, Labute returned to directing another of his own plays, completing what I've already dubbed his 'trilogy of cruelty,' with 2003's The Shape of Things. Starring a young Paul Rudd and Rachel Weisz and painfully mis-marketed as a kind of teenaged rom-com (it isn't one), it struggled to find any kind of audience and didn't blow away the critics, either. Which is a shame, because there is something pretty interesting and original here. Admittedly it is, I think, the most flawed of the informal trilogy, and probably the most pedantic, suffering from some thinly written ancillary characters whose place in the story feels a bit forced, some awkward musical cues, and some pacing issues. Still, the central relationship that develops between Paul Rudd's Adam and Rachel Weisz's Evelyn (a not too subtle nod to Adam and Eve) is not an uninteresting one. Dorky, out-of-shape art gallery guard Adam is inspired by the affections of his mysterious new paramour and aspiring artist Evelyn to undergo a series of self-improvements; but as he grows more confident and more desirable, his morals become more flexible in turn. Saying much more than that would be spoiling things central to the film's particular twists, but suffice to say their relatively innocuous seeming relationship culminates in an unexpected and gutting climax that reveals all has not been quite as it seemed. For me, the strength and originality of the film's central conceit allows me to overlook the fact that it is a somewhat clunkier effort than either In the Company of Men or Your Friends & Neighbors before it; and some missteps aside, I think it's well worth seeing as a bookend to the other two.

25.02.19

YOUR FRIENDS & NEIGHBORS

dir. Neil Labute, 1998

"Common decency dictated the whole thing."

Fresh off of his adaptation of his play In the Company of Men, Labute released Your Friends & Neighbors, which interweaves the relatively mundane stories and infidelities of a group of loosely associated characters. With a level of late-90s hyper-cringe only rivaled by the work of Todd Solondz, Your Friends & Neighbors can be a taxing watch if you're not up to it. Aaron Eckhardt plays against type this time as a doofy husband having performance problems in the sack. His wife, a dorkily charming Amy Brenneman, strays into the creepily willing arms of his friend -- an eyebrow-raising Ben Stiller at his very cringiest, a nerve-gratingly whiny English professor with a perpetual lascivious eye on his own students. He has some sexual performance problems of his own, particularly with his frigid, bitter girlfriend played by an icy Catherine Keener, who's own interests are straying to a local art gallery employee played by the lovely Nastassja Kinski. Rounding them all out and poking into their criss-crossing lives is this entry's resident sociopathic misogynist, a perfectly cast Jason Patric, whose extended and disturbing mid-movie monologue about his "best f*ck" would have, in a parallel universe, earned him an Academy Award. (And which is further brought home by a subsequent scene's brilliant punchline to the whole set-up, in which Ben Stiller's character inadvertently tops an un-toppable story with a simple truth).

In essence it's all a fascinating, darkly funny -- but often difficult-to-watch -- tapestry of sexual selfishness, impotence, casual cruelty, emotional immaturity, and various forms of infidelity. There's little in the way of admirable or even likable characters to be found, though some are more sympathetic than others, and it is definitely not going to be a movie to all tastes. You have to have a high tolerance for irredeemable social discomfort to stomach these characters as an ensemble.

Where In the Company of Men was focused and tightly-knit enough to bring its strange plot to a kind of coldly transcendent climax and resolution, Your Friends & Neighbors feels a little less certain about where exactly to land. It does find its way to a series of relevant confrontations between the various main characters, all of which are interesting, all of which are cringe, and some of which make a little more sense than others. Fascinating and repulsive, it remains a truly unique mosaic of social dysfunction and is a good "middle film" to what I previously referred to as Labute's "trilogy of cruelty," bookended by In the Company of Men on the one side, and 2003's The Shape of Things on the other.

25.02.18

In the Company of Men

dir. Neil Labute, 1997

"I don't trust anything that bleeds for a week and doesn't die."

(Minor/vague spoilers). Clearly inspired by the talky, testosterone-driven work of David Mamet, playwright Neil Labute's directorial debut follows a pair of cringily unlikable corporate company men who, ostensibly recently rejected by the women in their lives, hatch a callous plan to take meaningless revenge against an unsuspecting woman by simultaneously courting her, and then confronting her about seeing both of them at once and dropping her from their lives; but as the set-up unfolds, not all is quite as it seems. Malloy plays the mousy, nerdy, push-over tag-a-long to Eckhardt's obnoxiously confident misogynist, who hatches the pointlessly cruel plan as a diversion for the pair during a six week off-site company assignment. Loosely inspired by an excellent 1992 French movie called Un Coeuer En Hiver by Claude Sautet, you will find yourself cringing -- and maybe inadvertently laughing -- as the pair's heartless plot unfolds by way of a deaf typist (played wonderfully by Stacy Edwards, who brings a genuine humanity to the proceedings as the sweet, plausible Christine). This premeditated prank of a love triangle leads to some interesting revelations about each of the characters in turn, culminating in a shocking and unsettling climax that offers little in the way of redemption for its heinous central characters. This was Aaron Eckhardt's breakout role, and I still think it is one of the best performances he's ever given. In fact he was so convincing as the heartless instigator Chad, that, as the story goes, a woman walked up to him and slapped him after an early screening, unable to separate the actor from the character he'd just portrayed on screen. Eckhardt tried to explain that it was simply a character he was playing, but she responded "No! I hate YOU!"

Certainly this is not a movie for everyone or the easily offended, but I find its unflinching investment in a portrayal of unapologetic misogyny, casual cruelty, and power dynamics hypnotizing and gutting. It's rare to be put so completely and unwaveringly in the POV of what would be reviled antagonists in any other movie, and it's kind of a unique treat in its twisted, cringey way.

This also constitutes the first of what I see as Labute's informal "trilogy of cruelty," further comprised of 1998's Your Friends & Neighbors, and 2003's The Shape of Things.

25.02.18

By Brakhage

dir. Stan Brakhage, 1955-2003

I tend to think of Brakhage as a kind of Merzbow of cinema. A prolific experimental filmmaker given fresh life thanks to Criterion's excellent anthologies of his work, Stan Brakhage seems to be best known for his technique of hand-painting rolls of film to create the equivalent of living, moving expressionist paintings; and they are really quite beautiful. Some of his work, to be sure, features characters and identifiable places and scenes -- mostly documentary-style footage taken from his real life (sometimes intimately or shockingly so, with actual footage of his child's birth on one hand, and a visually unflinching exploration of a morgue on the other) -- but for me it's the various hand-painted short films that are the star of the show. They're just so beautiful; seeing them projected on actual film must be a real treat, but Criterion does a great job capturing the essence of that feeling with the way these are rendered here. These are mostly soundless creations, which is a little bit of a shame, because when he does integrate sound it's lovely weird-o experimental stylings that fit the material quite nicely. Always worth putting on if you want to drift away into a world of pure visual ambience.

25.02.17

TWIN PEAKS (Season 3)

dir. David Lynch, 2017

"What year is this?"

25 years after the original, kismet saw fit, and David Lynch returned to the world of Twin Peaks for a third and final season. I remember feeling quite skeptical at the time of its announcement and airing, far from convinced of the value in Lynch returning to the project. But by the close of its opening dual episodes I was firmly on board, and within a couple more episodes, completely enchanted. From there I spent each week eagerly awaiting the release of each new episode in turn, mesmerized for the full duration of its 18-episode run. I would watch each episode 2 or 3 times over during this initial run, only to later rewatch the entire series with my wife, so I only skimmed over some of my favorite portions for the purposes of this belated review, but it was enough to remind me of why Twin Peaks Season 3 might just be my very favorite David Lynch creation -- an 18 hour magnum opus, shot like an 18 chapter film, and managing the improbable feat of besting the original two seasons in quality and overall vision. While there is certainly a fair amount of connective tissue and easter eggs for fans of the original two seasons and the Fire Walk with Me movie, Twin Peaks Season 3 stands in many ways entirely on its own and feels like a completely unique creation. Every weird new entry seemed to bring a new multi-faceted expressionist look at an increasingly empty, soulless America, while advancing the unlikely story of "Dougie," a new shell-character for a special agent Dale Cooper trapped between two conflicting realities and times. Those expecting the return of their favorite FBI agent could be forgiven for finding the protracted adventures of "Dougie" (and Cooper's other 'evil Coop' doppleganger, an amusingly mullet-sporting bad boy of mysterious intent) a bit frustrating -- Lynch continually teases us with the potential return of Cooper proper, and eventually delivers it, but takes his sweet time and the majority of the season getting there. But a part of the show's strength is in challenging the viewer's nostalgia-fueled desire to return to the Twin Peaks universe as it was -- time has moved on, and we existed now in a perhaps not-so-brave new world, as of 2017. Season 3 tells a story intended for now, rather than trying to hopelessly recapitulate what worked in 1990.

And what a story it is. By 2017, with the wild Inland Empire behind him and reunited for Twin Peaks with the slightly more grounded Mark Frost, Lynch had found what I consider a nearly perfect balance for his signature weirdness. Deeply ambitious, frequently funny, periodically horrifying, and always captivating, there is just enough conventional storytelling at play here to rope the viewer along through Twin Peaks' increasingly surreal hoops. But the hoops are definitely surreal ones, and with Showtime giving Lynch complete creative control over the show's return, he takes Season 3 to places he only could've gone in his wildest dreams in the more network-TV-oriented Seasons 1-2, including a mid-season mind-blower revolving around the secret evils unleashed by the atomic bomb. Each episode is a little mini-movie unto itself, each with its own closing musical number (some of which are really terrific and which turned me onto some new bands) and none of the them disappoint, straight through to the expectedly confounding but ultimately somehow strangely perfect climax. If there's a weak link for me personally, it was the sometimes dodgy CGI special effects. At times Lynch gives them a wonderfully home-spun, absurdist sort of glory, but at other times, well ... they just come off as dodgy CGI. This is a minor nitpick however.

A whole book could be (and probably has been) written about Twin Peaks Season 3, and no synopsis can really do it justice -- across its 18 hours, there is just so much food for thought, so much to cover, so much that is supremely unique, so much to attempt to decode and analyze. But anyone who blew over this one as a needless "reboot" -- particularly any Lynch fans who did so -- you absolutely need to make the time for this one. Take it on its own bizarre terms and let it rope you into its world ... it is the most expansive and thorough piece of surrealism Lynch ever created, and while I am deeply saddened by his passing, I couldn't imagine a higher note for him to have gone out on creatively.

25.02.16

INLAND EMPIRE

dir. David Lynch, 2006

"Strange, what love does."

Inland Empire is one of my favorite Lynch films, and I think one of his scariest; I'm a bit more in the minority opinion on this one, but I consider it one of his masterpieces. It is definitely one more for fans than non-fans, with Lynch operating at his most abstract, his most surreal, his most indulgent, and his most deliciously labyrinthine. I can think of no other movie -- even among Lynch's -- that better captures the feeling of being lost in a dream (or perhaps, nightmare); and with the extended footage, it is a nearly four hour dream, so there's plenty of room to lose yourself in its many corridors. Shot entirely on digital, you might think it would lack something of the polish of his other feature films -- and you'd be correct -- but Inland Empire revels in its own fuzzy grit, and seems to mark an epiphany of a kind for Lynch when it comes to the unique strengths and freedoms of digital filmmaking. Some people find Inland Empire exhausting, but for me, the majority of its highly bizarre sequences prove eerily effective and memorable, and for something as abstract as it is, I think it coasts along relatively watchably, provided one can sort of let go and give oneself over to its strange, scary spell. Grace Zabriskie shines as usual in one of my favorite of her numerous Lynch performances, as a bizarre "new neighbor" who introduces herself in surreal fashion to our tentative heroine, a rich starlet (Nikki) up for a big role played by Laura Dern. Nikki lands the role and is warned by her director (an amusing Jeremy Irons) that the script they are working off of is cursed. The set then begins to take on a reality-jumping life of its own, and it just gets stranger and stranger from there. Characters begin to meld in and out of one another, film reality and non-film reality blur, acting and non-acting; bunny people weave in and out of the proceedings, dance numbers come out of nowhere, time shifts strangely back and forth and sideways, and a variety of sub-stories and new characters are introduced into what becomes an increasingly dense tapestry of broken dreams, gypsy folk-tales, prostitution, infidelity, domestic violence, unplanned pregnancies, hypnotism, and murder. All of Lynch's surreal tricks are fully charged and on display, here, startling and terrifying and confounding the viewer at every turn. Like Mulholland Drive and Lost Highway before it, there is the sense that there is a potentially coherent story (or stories, I would say) that could be extracted and decoded from this cryptic maze, with a little work -- at least up to a point. And like those movies before it, Inland Empire greatly rewards multiple attentive viewings and careful analysis. On the most basic level, taking the "inside-out" structure employed with Lost Highway and Mulholland Drive and applying it to what's here, my own interpretation is that we have a story of a young woman who comes to Hollywood with her husband and with dreams of stardom, but who is reduced to prostitution to make a living. A resulting unplanned pregnancy (not the husband's) tests the strength of their bond. In my reading of it, we have a happy ending, in which the couple moves beyond the how/what/why of the child's conception, assassinate the spectres of jealousy and guilt, and dedicate themselves to raising him as their own, putting the past in the past.

Now, even if my (highly arguable) baseline interpretation is valid, there are a host of other subplots and side-mazes and strange clues and refractions and symbols to be decoded and analyzed much further; I think we actually have a cross-section of different stories going on here, and like an epic dream, it's easy to feel no analysis, no matter how thorough, will ever quite get to the bottom of Inland Empire's many mysteries. To me, much like an indecipherable dream nevertheless rich with meaning, this is part of the joy of it. If you haven't seen this one in a while, or had mixed feelings about it the first time, I'd urge you to revisit it, and also to take the time to indulge in the "More Things that Happened" featurette, which includes nearly an hour of extra/cut scenes, some of which are truly memorable and that just add to the hypnotizing miasma of the whole.

25.02.14

MULHOLLAND DR.

dir. David Lynch, 2001

"No, you're not thinking. You're too busy being a smart aleck to be thinking."

Receiving mixed reviews upon its release, many now herald Mulholland Dr. as David Lynch's masterpiece -- and I tend to, generally, agree; it's definitely in my top 3, and depending on my mood and thinking at the time, would probably often be #1. Initially intended as a pilot for a new TV project, Lynch ended up turning Mulholland Dr. into a feature film instead. Elaborating on the identity confusion and fantasy realities played with in Lost Highway, Mulholland Dr. sees Lynch grabbing the idea of an inside-out expressionist narrative and taking it to its apex. From the visuals to the story to the music and sound design, Lynch is firing on all cylinders here, balancing his signature strangeness with just enough accessibility to rope the viewer thoroughly into his bizarre, foreboding dreamscape (the now infamous Winkie's scene alone is worth the price of admission). It's Lynch weaving his particular brand of terrifying and amusing poetry at its most effective, but for all its initially confounding weirdness, Mulholland Dr. proves surprisingly decodable on repeat viewings, at least with a little viewer investment -- and I think that is to its credit. It's abstract enough to be open to interpretation, but coherent enough to be satisfying as an ingeniously inside-out whole. Ultimately many would agree that what we have here -- at least fundamentally, on one level -- is the tale of a bitter jilted lover, an aspiring actress named Diane (a multifaceted role played wonderfully by Naomi Watts, in her breakout turn) assassinating her more successful paramour. The movie begins with (among other things that deserve a separate discussion) Diane's extended (and ultimately heartbreaking) fantasy and dream of undoing what she's done -- a romantic escapade in which said paramour is spared from her assassination and finds her way to a fantasy version of Diane (named Betty) as an amnesiac femme fatale in need of rescue. As the two consummate Diane's imagined love between them and embark in a self-destructive bit of sleuthing together, cracks begin to show in the facade of this dreamscape; and with the help of a surreal and mysterious cowboy, the whole thing crumbles as Diane finally awakens to the horrific and inescapable truth of what she's had done. Peppered into the proceedings we have (among other bizarre set pieces, like a paid hit gone amusingly wrong) a weirdly self-referential side-story of a director losing creative control over his own movie. This cleverly ties into the central story but invites its own speculation as a sort of surreal parody of the machinations of Hollywood and (perhaps) Lynch's experiences therein. Ultimately it's the kind of movie that invites and rewards deep repeat viewings and analysis, and has a website devoted to it. Thanks to its intriguing connective tissue, it falls a little less readily into the "weird for weirdness sake" criticism that (sometimes understandably) plagued Lynch's previous work (though it is undoubtedly, wonderfully weird). I'm always curious to hear other people's impressions and analysis of this particular movie, but bottom line, for me, it all works beautifully and casts a unique spell, rewards close attention and multiple viewings, and highlights Lynch's many strengths as a surrealist and filmmaker.

25.02.12

LOST HIGHWAY

dir. David Lynch, 1997

"I like to remember things my own way."

After a five year break, with Twin Peaks firmly behind him for the time being, Lynch debuted the startling Lost Highway, which begins what I tend to think of as a kind of spiritual trilogy (comprised additionally of Mulholland Drive and Inland Empire). All three movies revolve around confused interchangeable identities, and the way I tend to interpret them, all three deal with constructed fantasy worlds crumbling away to reveal horrific underlying realities. In Lost Highway, impotent wife killer Fred imagines himself a young, virile bad boy, and their respective identities and destinies interweave and self-destruct in labyrinthine, Escher-like ways. Lynch's tricks and quirks and odd sense of humor are pretty well-established at this point in his career, and he navigates the bizarre hall-of-mirrors-like landscape of Lost Highway with cozy, creepy expertise. I find the first half of the movie particularly captivating, with its expansive dreamy silences, somewhat wooden acting, and liberal use of negative space (both visually and temporally), and of course the unforgettable, mime-like mystery man played by Robert Blake -- not to even mention the beautiful, ethereal banger that opens the movie, by David Bowie. The second half, revolving mainly around Pete, drags just a little, but still delivers plenty of interesting sequences and strange twists. (It's worth noting that the same exact premise that begins this movie -- that of a well-to-do couple receiving anonymous videotapes of the outside of their home -- likewise serves as the foundation of Michael Haneke's exceptional 2005 film Caché, which takes the set-up in a whole different direction).

25.02.10

TWIN PEAKS: FIRE WALK WITH ME

dir. David Lynch, 1992

"When this kind of fire starts, it is very hard to put out."

Lynch doubles down on all the weirdest and most surreal aspects of the world of Twin Peaks in a bizarre prequel critically reviled at the time of its release. It's since enjoyed something of a re-evaluation with a lot of Lynch fans coming to its defense, and some heralding it as one of his best films. Personally I fall somewhere in the middle -- I wouldn't rank it among his very best, but it sports some really incredible and chilling sequences and tons of surreal Lynchian quirk. I actually quite enjoyed Chris Isaak as the super chill special agent Chet Desmond in the opening segment of the film, and Ray Wise and Grace Zabriskie give their most electrifyingly weird performances yet as Laura's troubled parents. One jarring element of the movie -- apart from the fact that its cast of supposed teenagers are all clearly in their twenties and thirties -- is that a main character, Donna, played memorably by Lara Flynn Boyle in the TV show, is now replaced with an entirely new actress. In addition to not liking the "new Donna," I also don't particularly like Laura Palmer as an actual character, or the actress that plays her -- she always seemed more effective to me as an idea(l); so a movie centered around her actual activities in the days prior to her death leaves me, fundamentally, a little ambivalent. That said, there are a number of unforgettable moments and many effective stabs of Lynchian horror peppered liberally throughout what is unquestionably a work of considerable imagination, if not one likely to satisfy those looking for clean resolutions to the questions left open by the TV show. Indulgently surreal, periodically captivating, sometimes horrifying, often meandering, frequently bewildering, occasionally flat, and sometimes tedious, Fire Walk With Me remains, for me, a mixed bag of Lynch both at his best and at his most exhausting.

Also: there is an hour and a half of deleted and extended scenes to FWWM called 'The Missing Pieces,' which is peppered with interesting little extra bits -- but the stand out for me is what has to be the weirdest boxing match I've ever seen, between special agent Desmond and Sheriff Cable. Worth it for that alone.

25.02.09

TWIN PEAKS (Season 1-2)

created by David Lynch & Mark Frost

Prior to Twin Peaks, I don't think there was anything this quirky, strange, mysterious, or captivating on network TV, and the show's influence resonates to this very day decades later. For all that might be said about the story and plot, it's Lynch's ingenious focus on the ambient details of Twin Peaks' world that particularly struck me, revisiting it; it simply wasn't something any other show had done. The hum of the ceiling fans, the soft roar of a fireplace, the tumult of the waterfalls, the sparks of the saws at the mill, the wind in the trees, the strange focus on electrical devices -- all these little things were given a uniquely palpable feeling of significance, creating a universe both cozily inhabitable and weirdly foreboding. And of course, not enough can be said about the music -- Angelo Badalamenti's score is absolutely incredible and was undoubtedly integral to the initial success of the show. It has to be the best score for a TV show of all time, with its various riffs and themes effortlessly summoning feelings of dreamy nostalgia, dark foreboding, ethereal beauty, and jazzy mystery. Combine it with Lynch's knack for surreal quirks and unusual and unforgettable characters, and you wind up with something remarkably special, surpassing to my mind the interesting but more limited worlds created in Blue Velvet, or Wild at Heart.

It's a shame Lynch did not have the universal creative control he would exercise in the much later Twin Peaks Season 3. While the show as a whole is a fascinating creation, to me, the portions of the series written and directed by Lynch personally are the easy highlights, which include the pilot, the episode introducing the Red Room, the episode revealing Laura's killer, and the bizarre and controversial finale. The pilot episode particularly shines, and I have a special love for the extended international cut, which ran nearly two hours -- it had a rushed and forced-feeling ending that (sort of) reveals Laura's killer, but I still prefer it to the condensed American version. That little bit of extra time to stretch itself out pays off and includes key moments that make it a creation rivalling Lynch's best film work. It's one of my favorite things Lynch made. I used to have a copy of this version of the pilot on VHS, but it's long gone -- if anyone knows of a digital copy they can point me to, please do!

The well-known consensus is that the show kind of lost steam in its second season after Laura's killer is revealed, and I agree with that. The show as a whole is something of a mixed bag with its various writers and directors, some faring better than others; but it especially loses direction (and an important center of gravity) after the central mystery is solved. The directors sitting in for Lynch beyond that pile on the quirk without possessing his understanding of how to make the quirk work, and it all gets a bit overly wacky and loses its edge. Still, warts and all, there was nothing else like Twin Peaks before it came along and it remains one of the most fascinating examples of serialized network television to this day.

25.02.08

WILD AT HEART

dir. David Lynch, 1990

"It's just shocking sometimes. When things aren't the way you thought they were."

This world of hot pink and snakeskin jackets and stiletto heels and dusty yellow roads and blazing fire is one of maybe two Lynch films I was never really able to entirely get into. Highly original and full of weird moments and twists, with a definite (and strangely, Wizard of Oz influenced) vision, I'm sort of hopeful each time I return to it (this was maybe my fourth) that I'll fall under its spell or find some hook or key I previously missed that'll make it all work -- but, to date, it hasn't happened. I always find myself impatient and a bit agitated by it while I watch, and am unpleasantly exhausted by the time it's over. Laura Dern works as the bubby Lulu and Nicolas Cage is vaguely amusing as the Elvis-loving Sailor; Willem Dafoe is certainly memorable as the grotesque Bobby Peru, and Grace Zabriskie as a creepy, crippled villainness. But they just don't have a whole lot to do that makes sense or resonates for me, and most of the other characters feel pretty pointless and underserved. What little story there is proves incoherent and unsatisfying. Still, even having said this, it does, like everything directed by Lynch, remain worth seeing for its considerable uniqueness.

23.02.04

BLUE VELVET

dir. David Lynch, 1986

"I'm seeing something that was always hidden. I'm involved in a mystery."

Many people regard Blue Velvet as one of David Lynch's masterpieces. For me personally, it never quite captured my imagination the way much of his other work did -- maybe in part because I only saw it after seeing a number of his other films first. It's not quite as mysterious or engrossing as something like Lost Highway or Mulholland Drive, not as quirkily fun as something like Twin Peaks (or as horrifying or weird as the best moments in Fire Walk with Me), not as moving as The Elephant Man, not as dark and dreamlike as Eraserhead or Inland Empire. I wanted to spend a bit more time in its world and in its mystery than the time allots for -- I wanted to get to know these characters a little more, and understand their relationships a little better. Still, I'm a bit jealous of those who had the experience of going into this movie blind back in 1986, perhaps only knowing Lynch from The Elephant Man or Dune if at all -- not knowing what to expect, not realizing they were about to see something unlike any other film they'd seen. It follows the amateur sleuthing adventures of a young man (Kyle MacLachlan) and his friend and budding love interest (Laura Dern) as they investigate the possible circumstances behind a real severed human ear that Jeffery (MacLachlan) finds in the woods on his way home one afternoon. This leads them to the seedy side of town, where desperate femme fatales, gas-huffing sadists, and a variety of other n'ere-do-wells await (with their fast cars and cigarettes and Pabst Blue Ribbon beer all fueling a basic disregard for human decency!). Sure of hand and with a definite vision, and a lot of the same creative seeds that would be integral to his other creations, Blue Velvet remains a true original that you should definitely see if you never have.

25.02.03

DUNE

dir. David Lynch, 1984

"Without change, something sleeps inside us, and seldom awakens. The sleeper must awaken."

Though Lynch disavows his most commercial creation on the basis that he didn't have final cut -- a mistake he would apparently never repeat -- I remain a considerable fan, and the first half of the movie, at least, is frankly awesome, creating a foreboding and epic sci-fi world unlike any other on celluloid. Lynch again manages to navigate a relatively accessible story without sacrificing his blisteringly unique sense of style and tone, and the film is full of delightful Lynchian idiosyncrasies and charming (and sometimes horrifying) practical special effects. Unusually dreamlike for a science fiction adventure movie, and filled with delightfully weird aesthetic choices, Dune really casts a spell. It is unfortunate that it does admittedly fall apart a bit in the second, messier half, which plods along somewhat tediously, and features some pretty uninspired battle sequences. Still, this remains my favorite Dune adaptation by a mile -- the bloodless recent Villeneuve two-part snoozefest is not even in contention here. It's a shame Lynch was so embarrassed by this one, because despite its flaws, there remains a ton about the movie to love. Initially mocked and even reviled for some time, many people seem to now be coming around on how special it actually is. Imperfect for sure, but still profoundly original and well envisioned, with a tone unlike that of any other mainstream sci-fi picture out there.

25.02.02

THE ELEPHANT MAN

dir. David Lynch, 1980

Thanks to Mel Brooks knowing an artistic genius when he saw one, Lynch graduated directly from Eraserhead to this slightly more accessible, Academy-ready sophomore film, but did so without compromising any of his originality, tone, personal interests, or unique stylistic devices. The result was a strange and heart-wrenching breakthrough that garnered eight Academy award nominations, assuring Lynch a continuing career in Hollywood (with George Lucas famously offering him the director's chair on Return of the Jedi). Charting the wildly disfigured John Merrick’s journey from mute circus freak to eloquent society man, Lynch carefully balances sentiment, curiosity, empathy, and horror in this loosely biographical film adapted from Frederick Treves' The Elephant Man and Other Reminiscences (1923) and Ashley Montagu's The Elephant Man: A Study in Human Dignity (1971). While not my personal favorite of Lynch's work, it is really an impeccable, moving adaptation full of excellent performances and, like Eraserhead, it has a timeless feel and holds up well to this day.

25.02.01

ERASERHEAD

dir. David Lynch, 1977

This was far from my first time visiting the world of Eraserhead, but it continues to hold up better than ever. For what was in essence a protracted student film, it remains astonishing how complete, assured, and utterly original Lynch's aesthetic vision is in this low budget freshman outing. From the stellar home-spun sound design to the impeccable black and white imagery to the impressive practical special effects to the bizarre, nuanced performances of its small coterie of amateur actors, every surreal turn here simply sings with the strength of an astonishingly self-assured and deeply original personal vision, which for all its weirdness, tells a fundamentally coherent (if expressionistic) story about male alienation in the face of an unplanned family. In my experience there has simply never been another movie remotely like Eraserhead, and in my estimation this dark and beautiful and highly personal dream remains one of the greatest existing works of filmic surrealism we have. Truly one of a kind; the master will be sorely missed.

25.01.31

RED ROOMS

dir. Pascal Plante, 2024

Strange, sleek, cold, and rather novel approach to what could have been a very cliche murder mystery about a man on trial for livestreaming a set of snuff films, and the acts enacted within those films. The protagonist, a fashion model who is for unknown reasons obsessed with the case and who is attending the trial daily, and who gradually befriends one of the alleged killer's sycophants, becomes a strangely and effectively gripping character as the film unfolds. But when all is said and done, it perhaps leaves more open questions than was necessary, and certainly than is satisfying. Absolutely held my attention and drew me in start to finish, however, with excellent performances and a unique vibe. I was just left wanting more -- more of the characters, more explanation re: motives, more everything -- but it leaves room for your own imagination to do some of the work to fill in the gaps, and that's not the worst position to be left in.

25.01.09

JOKER: Folie à Deux

dir. Todd Phillips, 2024

Ya know, I wasn't particularly a fan of the first Joker, but I feel the need to give them some credit for committing to the bit and trying something as bold as a musical for the sequel, and I actually think this is the better of the two films taken as a whole -- to the extent it perhaps even elevates the original film a little bit, by rounding out the picture that that film attempted to paint. At the very least, it's not quite as bad as many critics are claiming -- it has more characters than the first movie and the relationships between them are certainly not uninteresting (with Brendan Gleeson shining in particular as one of the prison guards) and the visuals and cinematography continually command attention. Some impressive (if somewhat head-scratching) set pieces bolster it as well, particularly in the final third (the getaway sequence in particular I enjoyed). The movie as a whole gives us a lot more time to get to know and invest in the Arthur Fleck / Joker character than the first film did -- maybe to a fault. Because none of this is to say it all exactly works, and it does kinda drag on. It never entirely lost my attention, but I felt like it was continually threatening to actually be very good, without ever quite nabbing the carrot. While I don't think it's as bad as the reviews would have you believe, it's also, like the first film, not quite as sophisticated as it thinks it is, and none of the musical numbers are all that memorable, which is a problem for a (semi)-musical. I don't know the Batman mythos and canon all that well, but everything here spirals into what was for me a puzzling and unexpected ending, which I won't spoil here. Its unexpectedness is not particularly a detriment, though -- I'll take that over the relative predictability of the first film, and I'll actually be thinking about this one for a bit. All in all, it's an unusual exercise that doesn't quite land or satisfy and that never really electrifies, but that I found generally more interesting than the first film, if probably a bit overlong.

24.12.29

SHIN ULTRAMAN

dir. Shinji Higuchi & Ikki Todoroki, 2022

"For some reason, Kaiju only appear in Japan. The international community wants Japan to foot the bill. Do you think our politicians can fight that pressure?"

With little meta-narrative nods and splendid kaiju designs that capture the fun and absurdity of the 60s' source material, this might be my favorite kaiju-oriented movie of a recent spat I've watched. It doesn't hurt that I was an Ultraman super-fan as a kid, so I have a soft spot, here. Shin Ultraman focuses on the patter between bureaucrats trying to contain the situational disasters posed by each new kaiju introduced; or, as the story progresses, to negotiate with the various extraterrestrials visiting Earth with various plans. The patter between characters is followed through some genuinely interesting camerawork that favors imposing, low-angle shots in between chairs and tables and other blocks of darkness that continually serve to keep the framing visually interesting even during the expositional segments. The dialogue is clever as far as it goes -- it knows how silly this all is, and doesn't try to take it seriously, but at the same time, refrains from irreverent parody. It's a reasonable approach to fundamentally shallow material and does the job of keeping things snappy and interesting, even if they grow a bit nonsensical by the end. The visuals are nice and cartoony and fun, and the sound effects sound like they were the same samples used in the 60s era show, giving the battles a nice retro vibe.

Unfortunately, it kind of loses steam in the second half; I was hoping for an increasingly impressive roster of kaiju battles, but instead got a variety of negotiations and a somewhat too-CGI-reliant finale in space (though it was fun as far as CGI goes). The first half of the movie contains all the best stuff. Definitely worth seeing if you liked the 60s show, though.

24.12.19

AMERICAN BUFFALO

dir. Michael Corrente, 1996

"I go out there ... I'm out there every day. There is nothing out there."

A day in the aftermath of a poker game that may not have been quite what it seemed, with a petty robbery in the works, American Buffalo is no Glengarry Glen Ross, but there's something oddly hypnotizing about listening to playwright David Mamet's grungy characters talk, talk, talk their cynical way around issues of trust, friendship and loyalty in the cluttered emptiness of an old pawn shop.

24.12.16

BODY SNATCHERS

dir. Abel Ferrara, 1993

This corny, phoned-in, low-budget sci-fi flick seems an odd move for Ferrara after 1992's cult hit Bad Lieutenant. The pods are genuinely creepy, though, with their hundreds of probing spaghetti-like tendrils, and the movie has some delightfully bonkers moments, like a climax in which a six year old boy is thrown to his dramatic green-screened death out of a helicopter (I mean sure, he's the 'pod' copy, but still), or Forest Whitaker's underdeveloped character having an unhinged, pill-chewing suicidal meltdown as the pod people close in on him. However, for the most part the characters generally are just about as shallow as their pod copies, and a fundamentally interesting theme is probed with little to no depth, so I can't really pretend there's much to recommend here beyond a few surprisingly unsettling moments and more than a few unintentional laughs.

24.12.15

DRIVE-AWAY DOLLS

dir. Ethan Coen, 2024

"Ladies, you're a day late and a dick short."

If there's an example of a movie being too high-energy for its own good, this has gotta be it, a plucky lesbo hippie road romp that makes Raising Arizona look like a Henry James adaptation. Joel Slotnik (you'd know him if you saw him) and C.J. Wilson (you wouldn't know him if you saw him) stand out as a pair of hired goons who can't get along, but as a whole, it was kind of a bad trip. That isn't to say it isn't impeccably made -- shot for shot, frame for frame, for better or worse, this is exactly the movie Ethan Coen wanted it to be, a master in highly questionable but unarguably complete control of his craft. Continually grating and aggressively trippy, but undeniably well made.

24.12.13

BOY KILLS WORLD

dir. Moritz Mohr, 2023

I adore H. Jon Benjamin, but I'm not sure narrating dystopian action-adventure movies is really in his wheelhouse, however cartoonish they might be. Colorful, hyperviolent, well-choreographed, and peppered with fun little ideas, Boy Kills World should be a lot more fun than it actually is. Its quirks never really work and its somewhat meta plot fails to really cohere into anything particularly memorable. Killer final boss battle though!

24.12.12

TITANE

dir. Julia Ducournau (2021)

I knew nothing about this movie going in except that Paul Thomas Anderson sung its praises in one of his interviews. It takes a lot to weird me out, but Titane managed the job pretty well. Aggressively bizarre and unpleasant and pretentious (perhaps to a fault) this beautifully directed if stomach-turning film is certainly some kind of religious allegory, though I wouldn't be the one to presume to try to tell you what it all means. The Christian concepts of God, Christ, forgiveness, and the relationship between man and machine are definitely among Titane's many high-falutin' themes, though. It's hard to know how to feel about this one fresh off an initial viewing. On the one hand, it is absolutely a one-of-a-kind experience with some unforgettable sequences by a director that clearly loves the unique language of film-making, and I can't say I've ever seen another movie quite like it (I particularly enjoyed the brain-poppingly weird dance number to She's Not There by The Zombies, and the soundtrack in general is killer). On the other hand, this is the closest a movie has come to actively nauseating me in a long time (and I just watched The Substance) and it's definitely Pretentious with a capital P. Fans of Cronenberg and Lynch and Gaspar Noe might all find a lot to enjoy here, but dive into it at your own risk. Difficult but fascinating, it's an unsettling, beautiful, horrible, head-scratching watch.

24.12.11

GODZILLA MINUS ONE

dir. Takashi Yamazaki, 2023

I opted for the black & white version, which I think was the right choice. Godzilla looked pretty fantastic -- just the right blend of being fundamentally true to the original design, while still being modernized enough to work in a way that wasn't intentionally corny. All the scenes featuring Godzilla were generally very cool, delivering a satisfying, awe-inspiring spectacle. The downside, of course, is that those scenes make up something like twenty minutes of the movie's 2+ hour run-time, and that the rest of the time we're saddled with a mopey, self-hating protagonist and a story that's 100% high-key melodrama. It's not the worst way they could've gone with it -- the high melodrama in and of itself reminds one of '50s filmmaking -- but, well. I don't know exactly what I would want from a modern Godzilla movie -- I'm fairly indifferent to the prospect of these continual remakes/revisitations/sequels -- but this wasn't exactly it. Still, it's superior to any of the American Godzilla movies (and it's not even really close).

24.12.10

CIVIL WAR

dir. Alex Garland, 2024